The following is an excerpt from a longer article published by Victor Canto, PhD, who serves as an economic consultant to TPCM. To inquire about the full article please visit LaJolla Economics website.

The decline in President Biden’s approval rating to below 40% from a high of 57% in March of 2021 has us wondering whether the President will pivot his policy and pursue greater bipartisanship if the Democrats lose control of the House and Senate after the midterm election. Of course, this decision could have ramifications for the next Presidential election in 2+ years.

Bipartisanship weeds out the most extreme components of legislation and only policy components with the most common ground survive. Unfortunately, bipartisanship has not been the driver of the most important pieces of legislation of the last few years which have passed with nary a single vote from the opposing party. In our opinion, this is an unfortunate and unhealthy development for our democracy.

In the long run the country is better off if the President is able to build a bipartisan consensus. But how can the party in power tell whether the President is building a consensus around his views? We believe that Presidential approval ratings send a clear signal of voter satisfaction or discontent, and absent elections, are the sole vehicle by which the voters have to express their views and opinions.

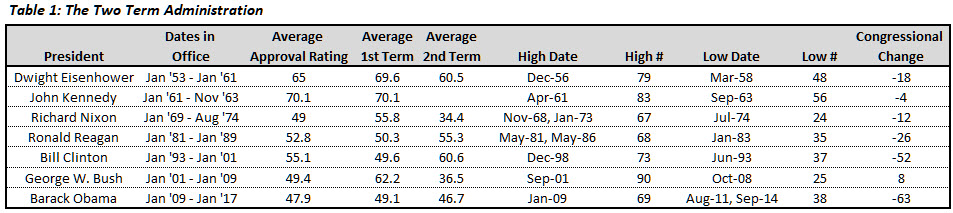

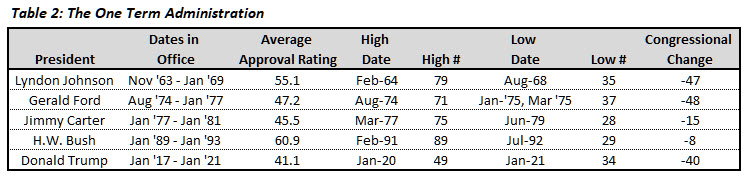

We looked back at the average approval ratings of different administrations as well as the peak and trough in approval ratings. We split the post war sample into two distinct groups: The two-term administrations in Table 1, and the one-term administrations in Table 2. The information presented yields interesting results. For the most part, administrations averaging an approval ratio below 50%, with a dip below 40% during the first term, saw reelection as an unlikely event. Unlikely, though not impossible, as seen by the elections of Reagan, Clinton, and Obama. The takeaway is that if low approval ratings occur early enough in the term, the administration can reevaluate and reorder its priorities.

We focus on the Reagan, Clinton, and Obama administrations as a guide to administrations who overcame low ratings early during their first term. The Trump administration is our guide to those who were unable to overcome these obstacles.

The Reagan Administration

Lower tax rates and regulations, a strong dollar and defense sprinkled with a large dose of optimism were the foundation of Reagan’s economic platform. During his first year in office the bulk of Reagan’s economic agenda was adopted in a bipartisan way, but the second year was not a smooth one. We attribute these difficulties to the implementation of the Volker-Reagan policy mix.

On the monetary side, Fed Chair Paul Volker never admitted publicly that the Fed would target a 2% inflation rate. The people had to figure this out based on the economy’s inflation performance. The learning process meant transitional adjustment costs. On the fiscal side, the gradual implementation of the tax rate cuts phased in over three years contributed to the recession the US experienced. The phasing in of a tax rate cut had the same effect on economic activity as does a sale at the store: why buy now when you can wait for better prices. This slowed economic activity and, in this case, deepened the recession. Many legislators urged the president to roll back his income tax rate cuts and eliminate the third year. But President Reagan decided to stand firm. In his 1982 State of the Union, President Reagan acknowledged the economic distress. Yet he pledged, “…I will seek no tax increases this year and I have no intention of retreating from our basic program of tax relief…”

In 1982, economic conditions deteriorated but President Reagan’s message resonated with the electorate and although the Republicans lost twenty-six congressional seats, the losses were much less than expected. By 1983, the bulk of the tax rate cuts had taken effect, the economy took off and the inflation rate collapsed to the 2% – 4% range. On the foreign policy front, President Reagan was also heavily criticized, but again, he stayed the course and his policies contributed to the USSR’s collapse. The economic and foreign policy successes fueled Reagan’s popularity and his approval rating during his second term exceeded the first term levels.

The Clinton Administration

The Man from Hope pursued a “progressive agenda” his first two years in office and attempted to implement it in a very partisan manner. He succeeded in increasing the top personal income tax rate with a party line vote, with not one Republican joining. Yet the administration was unable to pass what became known as “Hillary Care.” The economic and financial market response to the Clinton policies was tepid. During the first two years of the Clinton administration, the stock market barely appreciated, and the economy grew below a 3% real GDP growth rate. House Republicans under Newt Gingrich sought to gain advantage and crafted the so-called Contract with America. The contract resonated with the voters who were unimpressed by the lack of economic progress under Clinton and, quite possibly, also about the partisan manner the legislative agenda was implemented. Voters sent a clear message to the Democrats who lost fifty-four House seats, ten Senate seats, and control of both chambers.

To President Clinton’s credit, he heeded the voters’ message and pivoted to a bipartisan agenda. His “triangulation strategy” partially adopted the ideas of his political opponents, taking credit for them and thereby insulating himself from opponent’s attacks. Legislation passed in the latter half of his first term was bipartisan and included welfare reform and the signing of NAFTA. In his second term, Clinton presided over a lowering of capital gains tax rates as well as a balanced budget. The Clinton pivot fueled a strong economic performance. The US economy grew in excess of 4%, the inflation rate dropped to less than 2% and the stock market soared. President Clinton’s approval rating improved during the second term in spite of the 1998 impeachment proceedings.

The Obama Administration

As the 2008 election neared, the US was dealing with the fallout of the Financial Crisis. The economic response came from the Keynesian textbook with a significant increase in government spending aimed at stimulating aggregate demand. The Financial Crisis marked a new era of central banking as the Fed dramatically expanded its balance sheet and pursued a low interest rate policy. The expansion of the balance sheet financed much of the stimulus program adopted by the outgoing (Bush) and incoming (Obama) administrations.

Like Clinton, the Obama administration pursued healthcare legislation, “Obamacare,” as its most prized legislation, which again passed on a party line vote. Tax rates and the regulatory burden were increased through legislative and administrative measures. Subpar economic growth resulted and was dubbed the “new normal.”

Voters sent the Obama administration a strong signal of disapproval. Democrats lost sixty-three House seats and five Senate seats. Yet unlike President Clinton, the Obama administration did not pivot. It continued to govern in a partisan way and chose to pursue legislation through executive order both domestically and internationally. The most blatant example of this was the Iran deal that never made its way to Congress, was signed as a side deal and not an international treaty, and which was subsequently undone by President Trump.

The Republican sweep of Congress slowed the passing of legislation in Congress, leaving Obama complaining of having a “pen and a phone.” Executive orders and regulations became more common which slowed but did not stop the economic expansion. Positive real GDP growth with a low interest rate policy produced a rising stock market which was enough to carry President Obama to a second term where the partisanship continued as did the “new normal.” Not surprisingly, neither the voters’ approval ratings nor economic performance improved during the second term. The great irony of Obama’s two terms was that his policies resulted in a deterioration, not an improvement, of the distribution of income. The rich got much richer as income growth was meager while asset values (stock market) increased by double digits annually.

The Trump Administration

President Trump has the distinction of being the only president in the postwar period to not reach the 50% approval rating threshold. His combative and chaotic management style and campaign slogan to “Make America Great Again” was divisive. Yet his economic platform was pro-growth as it included a reduction in tax rates and regulations. Unable to consistently muster sixty votes to avoid a Senate filibuster, the Trump administration opted for a partisan approach. It used budget reconciliation process to pass tax rate legislation with no Democrat voting in favor. His style and tactics contributed to a drop in his approval rating to 35%.

The Trump administration’s low approval rating resulted in a loss of forty house seats and two Senate seats. President Trump opted to follow the example of the Obama administration by not pivoting its approach to bipartisanship and shifted his legislative priority to target “unfair trade practices,” especially China, by setting tariffs on imported goods and services and seeking to enforce intellectual property rights. China accused the Trump administration of engaging in nationalist protectionism and took retaliatory action. The trade war escalated through 2019, and Trump’s approval rating took a hit before an agreement was reached in early ’20 which led to an increase in Trump’s approval rating to a peak of 49% in May 2020. Two months later, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic and economic activity was significantly curtailed.

President Trump’s reelection bid failed owing to the pandemic but also to the acrimonious environment that he cultivated which intensified into the elections. Our interpretation of the election is that voters wanted the administration to temper its style, to pivot and cooperate with the opposition. President Trump chose not to do so, and he lost out on a second term.

Lessons learned…?

Despite difficult starts, President Reagan and Clinton won reelection and have the distinction of experiencing an improvement in approval ratings that exceeded an average of 55% during their second term. Although the Reagan and Clinton administration got to the second term in different ways, qualitatively both delivered similar economic outcomes: a bullish outlook and an improving economic environment.

President Reagan reassured the voters that his policies would work, and he stayed the course. Once the tax rate cuts took effects, the economic environment improved, and his popularity improved. The Clinton administration began with a partisan agenda. When the voters rejected it, the Clinton Administration pivoted and adopted a triangulation strategy that paid more attention to the structure of incentives. The strategy worked, the outlook and the economy improved, and President Clinton administration was reelected with approval ratings in his second term that grew past the 50% threshold.

The obvious conclusion is that it matters not where one begins, but rather where one ends. Bipartisanship, an improving economy, and hopeful future outlook are a recipe for reelection and voter satisfaction. However, as the Obama administration showed, these are sufficient but not the necessary conditions for reelection.

Both the Obama and Trump administrations had a first term average approval rating below 50% and paid heavily for their policy and approach at the midterm elections. Both chose to continue their partisanship, and their voter approval remained, on average, less than 50%. While President Obama won reelection, his refusal to pivot from his first term policies did not materially improve the economic environment nor did his approval ratings gain during his second term. President Trump also chose not to pivot, and he was subsequently not reelected. One way to interpret these results is that a sub 50% approval rating heading into elections is at best a 50/50 proposition as far as reelection is concerned.

President Biden’s decision

With an approval rating that is sub 40, it appears likely that voters will send President Biden a strong message at the midterm election with the Democratic party poised to lose seats in both the House and Senate which will make it impossible for the Biden Administration to purse a partisan legislative agenda. While Republicans will control the legislative agenda, President Biden controls the veto which is at best a defensive or blocking strategy. Without a veto override, the best partisan outcome for either side will be gridlock.

We are hopeful for a Biden pivot, but our reading of the tea leaves suggests that Clinton triangulation is an unlikely strategy for him to pursue. While early remarks in the recent State of the Union speech left us hopeful, it soon became clear in the balance of the speech that Biden was simply looking to rebrand his Build Back Better economic program. Further, Republicans recent attempt to hold a vote to end the emergency declaration on the 2-year Covid-19 pandemic suggests they may be equally as dug into partisanship. While the measure passed the Senate along party lines, the measure is unlikely to pass the House. But even if it did, President Biden has pledged to veto the bill and a veto override is an unlikely outcome. Why is this important?

The Biden administration has argued that the end to the Covid-19 emergency declaration would “…abruptly curtail the ability of the administration to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic.” A more cynical perspective would argue that the emergency declaration allows the Biden administration to keep control and implement policies that they would not be able to enact or implement if they were required to use the legislative process. The long running Iran negotiations adds another piece to the puzzle. A deal is unlikely to be reached on a bipartisan basis, and like the Obama administration, the Biden administration will attempt to pass it without Congress’ approval. From our viewpoint, the above suggests that there will be no pivot forthcoming from the Biden administration as it intends to stay committed to its economic and foreign policy.

The above illustrates that the Biden administration has time to pivot and adopt policies that improve its approval rating to the 50% threshold, or higher, and perhaps win reelection in 2024. Alternatively, it could continue its partisan way and roll the dice as did the Obama administration with reelection. We do not believe that the Biden administration will pivot, and as with the Obama administration, there is no reason to believe that the economic outlook is likely to improve.

In spite of the post Covid-19 recovery, there are clear clouds on the economic horizon, with Ukraine adding further uncertainty. The inflation rate is at a 40 year high just as the Fed has a new operating procedure and no one knows how it will react to an external shock. Recall that the 1970’s inflation coincided with a new operating procedure and an oil shock. Could a similar shock produce a similar outcome? The economy is growing but how much of that is a function of Covid-19 government relief and where will steady state trend growth rate settle? Our fear is that the higher tax rates and regulation of the Biden administration may create a new “new normal” that is no more pleasant than the prior one. Of course, the key question remains of whether voters will sign up for four more years…

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The information in this report was prepared by Timber Point Capital Management, LLC. Opinions represent TPCM’ and IPIS’ opinion as of the date of this report and are for general information purposes only and are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally. IPI does not undertake to advise you of any change in its opinions or the information contained in this report. The information contained herein constitutes general information and is not directed to, designed for, or individually tailored to, any particular investor or potential investor.

This report is not intended to be a client-specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon.

This communication is provided for informational purposes only and is not an offer, recommendation, or solicitation to buy or sell any security or other investment. This communication does not constitute, nor should it be regarded as, investment research or a research report, a securities or investment recommendation, nor does it provide information reasonably sufficient upon which to base an investment decision. Additional analysis of your or your client’s specific parameters would be required to make an investment decision. This communication is not based on the investment objectives, strategies, goals, financial circumstances, needs or risk tolerance of any client or portfolio and is not presented as suitable to any other particular client or portfolio. Securities and investment advice offered through Investment Planners, Inc. (Member FINRA/SIPC) and IPI Wealth Management, Inc., 226 W. Eldorado Street, Decatur, IL 62522. 217-425-6340.

Recent Comments